it is...precious to me

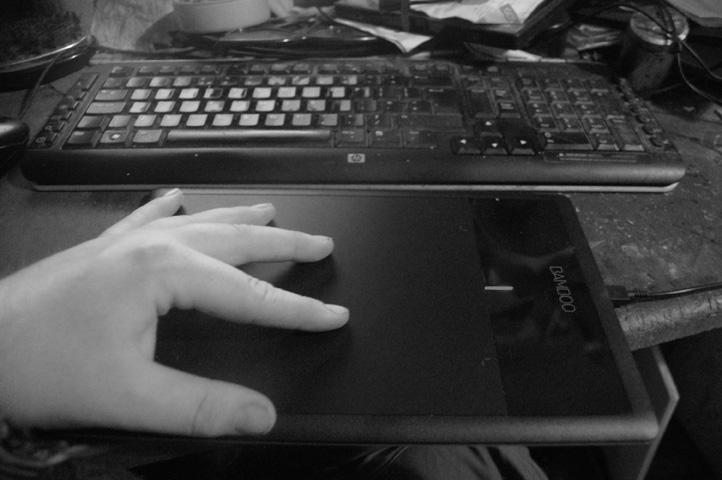

As I said in my previous post, it's astonishing how much I've come to rely on the use of a graphics tablet. I've been making digital art (or at least, using digital methods in creating art) for probably about 12 years now, the vast majority of it just using a mouse. Drawing with a mouse is fiendishly difficult (I've heard it aptly compared to drawing with a bar of soap), but a youth well spent with Unreal Tournament, Quake II, Team Fortress Classic, Battlefield 1942, Starcraft and other such delights had trained me well in its use. I had even tried using a graphics tablet before, many years ago; for some reason that time the disconnect between the screen and the drawing surface had just completely thrown me, and it hadn't worked. When I picked it up again, it suddenly all fell in to place. Of course, once you've used the stylus, going back to the mouse is impossible, and though the new Bamboo tablet is much smaller than my venerable old Intuos 1, it still seems to do the job adequately. I've just installed it and had a little play around, getting back into the feel of things, doing a quick drawing in a pastiche illustration style rather unlike my normal work:

We'll see about doing something a little more serious over the next couple of days.

As I was walking back from PC World with the new tablet, I came on to a train of thought about the value placed on digital art, a subject on which I'd like to pontificate for the rest of this blog post. Yes, I know I said I'd get around to explaining the walks and I will...later.

Now, this is all going to get a little political, so sorry for that in advance.

One issue that I have thought a lot about in my work over the last few years, but have never really successfully tackled head-on, is the issue of what I call 'precious materials bias' in art. Simply stated, precious materials bias refers to a set of attitudes or belief which privilege, in a critical sense, more expensive to produce works of art, in terms of both money and time, over less expensive works, irrespective of the level of skill and ingenuity employed, or (more pertinently to contemporary art) the cleverness of the concept or its execution. I call it a bias because it is neither even nor universal, more a tendency. It is particularly obvious in the seriousness with which artists in the 'lower echelons' of art, where name recognition and personal branding are less of a factor are treated*, and, sadly, sometimes very obvious at the university level. Consider the difference in respect accorded two painters, one who works with oil on canvas, the other in acrylic on wood. Or two photographers, one working in high definition digital and the other in large format with a wet darkroom. This is not, I should hasten to make clear, about how work is priced when it is put up for sale, but mostly about the initial critical respect given to the work.

This isn't an attitude that just exists in art, of course. The reason this was in my head was because of a conversaion I had just this weekend with a friend, a talented silversmith (you can see her work here), where this whole subject came up. She mentioned that she had always encountered a similiar attitude, where people would assume goldsmiths were more skillful craftspeople than her, simply because they had the money to splash on raw materials. Mentioning this to some other friends online, I had a film student remark about the way those who edited film using traditional machines rather than using digital prints were treated with more respect, and even an Information science post-grad remarking how she could always get her work treated with more respect if she got it printed off and bound. My silversmith friend opined that this is related to a cultural attitude that's been present in the Western world for a long time (we have a mutual interest in dark age historical re-enactment), and that in other cultures, people would rather buy a beautifully made copper bowl than a crudely fashioned gold bowl.

Digital art gets socked straight in the jaw by this bias. Once the admittedly somewhat expensive initial outlays have been made, digital art is free to produce, at least in terms of materials, and its cost in time is invisible. Even the subtle physical evidence of labour (overpainting, erasure marks, tooling marks) are smoothed over. If anything, the ubiquity of computers and digital technology over the last 10 years has decreased their use in art. Digital painting, particularly, has become synonymous with a particular sort of soulless photorealism, and with fantasy art, an association that has done neither digital painting or fantasy art much good (I say this, by the way, as someone who cares a great deal about fantasy art). This sort of digital painting takes full advantage of the medium, its smooth quality belying the many hours of work that it has taken to create. Whereas in most other areas of art a conscious and direct engagement with the physicality of medium and material is prized, digital art apparently has no physicality to enage with. Even when respected artists engage tentatively with digital media, there is a sense of the curiosity, that the works are simply a novelty. A perfect example of this is David Hockney's recent Royal Academy show 'A Bigger Picture' which had an entire room devoted to his iPad drawings. These drawings were refreshing, in the sense that Hockney has had the gumption to use digital brushes in a painterly manner, not trying to hide the medium as so many digital painters do. But there is also the definite sense that these drawings are on display despite being digital in origin. The fact that they are by David Hockney RA and that they are hanging in the Royal Academy is what makes you have to take them seriously, and that they were mostly presented in the form of large format giclée prints** probably didn't hurt.

All this is very important to me, because it is essentially a brick wall that my practice has started to charge in to head first. My artistic practice has been through quite a few evolutions and inventions over the past few years, but, essentially, until the end of the third year of my BA (which ended last year) my work was being realised in a fairly traditional form; large prints, drawings and pieces of text art designed to be displayed on sculptural forms in a gallery. For a number of reasons, this never really worked, and so in my Masters programme I decided to take a very different path. At first, my idea was to approach the slightly obscure format of the artist's book in a fairly traditional manner; producing limited editions of work, each hand-finished at the very least, possibly bound personally by myself, with the hand of the artist present. A reaction against the sterility of design, a celebration of the humanity of craft, etc. etc. etc. In the meantime, I decided to use print-on-demand services on the web (namely lulu.com) to help me realise some work quickly whilst I built up my technical bookbinding skills.

Thing is, all that's gone rather out the window. The more I progress, the more I realise what a potentially wonderful, and non-elitist, way of distributing art I have here, at least for the book format. There is no waste, there is no fuss, artwork is delivered straight into the hands of the audience. Furthermore, the books are living documents, not tied down to print runs; all I need to do is upload a new PDF document to correct or amend anything. To me, this all seems very exciting. I have always got the sense that, politically if nothing else, I am not suited to the conventional art world; but that's a terrible reason to not make art, isn't it? In every arena of human creative endeavour (think about music, ebooks, etc.), distribution models are being shaken up, old paradigms falling, something newer and stranger and, yes, perhaps less comforting and precise is emerging. We live in interesting times. I wouldn't dare to claim what I'm doing is revolutionary, but it is, I think, somewhat unusual. We'll see where it goes, shan't we?

Thing is, all that's gone rather out the window. The more I progress, the more I realise what a potentially wonderful, and non-elitist, way of distributing art I have here, at least for the book format. There is no waste, there is no fuss, artwork is delivered straight into the hands of the audience. Furthermore, the books are living documents, not tied down to print runs; all I need to do is upload a new PDF document to correct or amend anything. To me, this all seems very exciting. I have always got the sense that, politically if nothing else, I am not suited to the conventional art world; but that's a terrible reason to not make art, isn't it? In every arena of human creative endeavour (think about music, ebooks, etc.), distribution models are being shaken up, old paradigms falling, something newer and stranger and, yes, perhaps less comforting and precise is emerging. We live in interesting times. I wouldn't dare to claim what I'm doing is revolutionary, but it is, I think, somewhat unusual. We'll see where it goes, shan't we?

*For how things work at the upper level, Don Tompson's entertaining book 'The $12 Million Stuffed Shark' is as unbiased an introduction as you'll find.

**Giclée is a brilliantly posh sounding artistic term that essentially just means 'inkjet'. It just sounds less crass, because it's French. Bloody silly game this, isn't it?

Thank you SD, for referring to my Work and our conversation earlier. Your article is well written.

ReplyDeleteI have been following halfheartedly art at the upper echelons and quite frankly am not that impressed. Only the concept seems to be of paramount importance. As a craftsman I look at the actual work, where I then find out that in a lot of cases someone else actually creates the piece. Yet they never get credited.

To me art is a creation encompassing the concept, craftsmanship and a serious wow factor. My lack of vocabulary is letting me down here. What I mean by wow factor is that the art pulls the viewer/person experiencing it out of their everyday mental paradigm. That is they are engulfed in it... speechless.

If a work of art provides me with that experience, it makes no difference if it is on paper or on the screen, music or an awesome sunset. If it is made out of gold or copper.